While conducting two of the first independent evaluations of text-based online dispute resolution (ODR) programs in U.S. state courts, Donna Shestowsky and I found those programs promoted access to justice in some ways, but inhibited it in others. To help other courts, we wrote an article about how they might reduce potential barriers when developing and implementing their text-based ODR programs. The following is a summary of our advice from the article, “Access to Justice: Lessons for Designing Text-based Court-Connected ODR Programs,” which was recently published in Dispute Resolution Magazine, a publication of the American Bar Association.

Court adoption of text-based ODR allows parties to communicate asynchronously, at their convenience, from anywhere. This suggests that ODR has the potential to increase access to justice, particularly for self-represented litigants,[i] and could lead to increased efficiency and reduced costs for parties and courts alike.[ii] Conversely, however, for parties who lack digital literacy or access to technology, mandated ODR could instead benefit already advantaged parties and leave others behind. Furthermore, in some instances, mandating ODR could reduce access to justice by overriding consent and party self-determination.[iii]

The Texas and Michigan Programs

The programs we evaluated differed in the issues involved and the platforms used. In Collin County, Texas, we assessed a debt and small claims pilot program in a busy Justice of the Peace Court (JP3-1) that used the Modria platform. In Ottawa County, Michigan, we examined a program for post-judgment family matters brought to the Friend of the Court (FOC), an agency under the aegis of the Chief Judge of the 20th Circuit Court. The FOC used the Matterhorn platform. Both programs, however, were intended to be mandatory once the program was referred. And both required that the parties register and communicate via text on the ODR platforms.

Litigant survey responses suggested that many parties were unaware of the ODR program or did not understand its main features. When asked what would make them more likely to use ODR for a similar case in the future, half said more information.

Although the programs we evaluated used different ODR platform vendors, the platforms worked similarly and had comparable limitations. The platforms provided a chat space and permitted third-party facilitation or mediation. Neither was available to those with significant visual impairments or limited English proficiency. Both allowed only one individual per side to participate. This limitation meant that in Texas if a party had a lawyer, the lawyer participated alone. In Michigan, only parties could participate, and those who had lawyers were not referred to ODR.

Possible Reasons for Not Using ODR

Although ODR was ostensibly mandatory in both programs, the majority of parties in each court did not use ODR. In Texas, both parties to a case used the platform in only 81 of 341 cases (24%) referred to ODR. In Michigan, ODR use was twice as high: For the 102 matters in which caseworkers determined ODR was appropriate, 48% used ODR. In 26 of the 53 matters in which the parties in the Michigan program opted not to use ODR, at least one party did not register on the platform.

Survey and interview data suggest a few reasons parties did not use ODR. In both programs, staff indicated they did not send parties who lacked digital literacy to ODR, and litigant survey responses suggested that many parties were unaware of the ODR program or did not understand its main features. In the Texas program, of those who did not use ODR, only one survey respondent (out of ten) indicated having received information about the program. When asked what would make them more likely to use ODR for a similar case in the future, half said more information.

In survey responses for the Michigan program, parties appeared to lack a basic understanding of how ODR worked. Half of the 50 parties surveyed near the start of their matter did not know ODR was offered free of charge.

According to Texas court staff, litigants received information about the ODR program via the notice the court sent to them (or their lawyers) about their court date, and through an email or text from the platform when the court uploaded their case to it — if the court had their email address or cellphone number. Both the notice and the email lacked information about how ODR worked. Similarly, the Michigan program’s automated email and text, platform, and FOC website missed opportunities to educate the parties.

Implications for Courts

Despite their accessibility issues, both the Texas and Michigan programs had similar access to justice benefits. Our evaluations suggest that for those parties who use ODR, the process is convenient. We found that 72% of ODR use in Texas and 52% in Michigan occurred outside of court and office hours, i.e., at times not available to them in traditional dispute resolution methods. However, in both programs, many parties simply did not register to use ODR. In addition, 50% of ODR users who responded to our survey noted that they liked that ODR was easy to use. These findings indicate that ODR can increase convenience.

Nonetheless, our finding that some parties lacked information or had nontrivial misconceptions about ODR also suggests parties did not always make informed decisions about whether to participate. To enhance access to justice and self-determination, courts should incorporate a communications plan. The plan should:

- Specify how parties can learn about the program and detail what information court personnel should relay about ODR

- Indicate what information about ODR to include on the court’s websites and the ODR platform to educate parties about how to use ODR and its potential risks and benefits

- Outline outreach efforts to urge social services or other agencies to inform their clients about the ODR program

Additionally, courts should present information about ODR in a way that is comprehensible to individuals with low literacy. They should also explain the privacy and confidentiality implications of using ODR, especially regarding whether and how communications shared on the platform might be used in subsequent legal proceedings.

Further, ODR offerings should be accessible to all eligible parties. Courts should urge ODR providers to facilitate use by parties with visual impairments and limited English proficiency. Additionally, courts should direct parties who do not have reliable internet access to computers in the courthouse or other community locations — though as a result of limited business hours and privacy concerns, this solution is far from ideal.

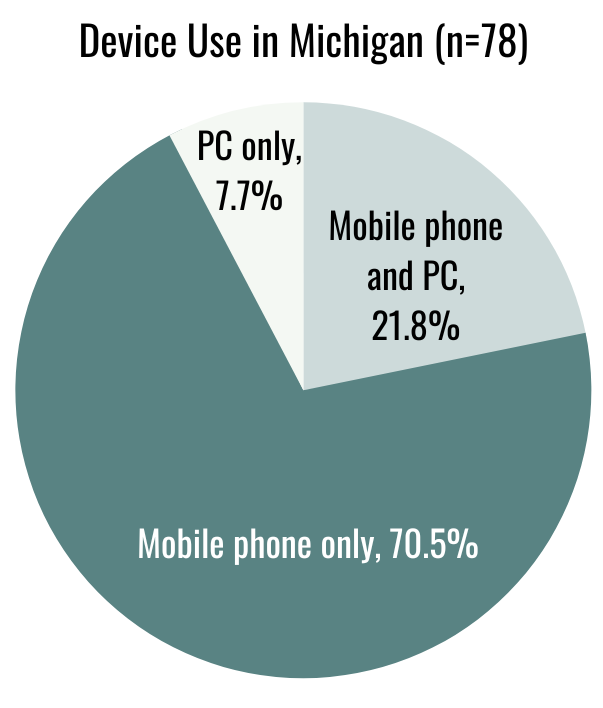

Courts should also ensure that text-based platforms are user-friendly for smartphone users. In the Michigan program, 71% of participants exclusively used a smartphone for ODR. (We did not have information on the devices Texas ODR participants used.) Yet our findings indicate that text-based ODR may be difficult for smartphone users. Courts should urge ODR providers to include in-app voice control to facilitate ODR use on smartphones generally, a change that might be especially important for individuals with disabilities that restrict their ability to type. Parties should also be able to participate in ODR with their attorneys.

Finally, courts should explore ways to maximize access to their platforms for those who lack digital literacy. Usability testing, similar to that conducted for Utah’s ODR pilot program,8 can help identify challenges and potential solutions for given platforms. Courts might also consider providing parties with links to web-based resources or trainings that could increase their comfort with technology.

Given ODR’s current technological limitations and the percentage of the population that continues to lack reliable internet access or digital literacy, ODR is not a panacea for the continued access to justice problem in the U.S. Additionally, our evaluations suggest that parties have different preferences for how to resolve their disputes. To enhance access to justice, and to advance party self-determination, ODR might best serve parties as part of a constellation of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) options rather than being the only form of court-connected ADR.

[i] Amy J. Schmitz, Measuring “Access to Justice” in the Rush to Digitize, 88 Fordham L. Rev. 2381 (2020).

[ii] Amy J. Schmitz, Measuring “Access to Justice” in the Rush to Digitize, 88 Fordham L. Rev. 2381 (2020).

[iii] Amy J. Schmitz & Leah Wing, Beneficial and Ethical ODR for Family Issues, 59 Fam. Ct. Rev. 250 (2021).