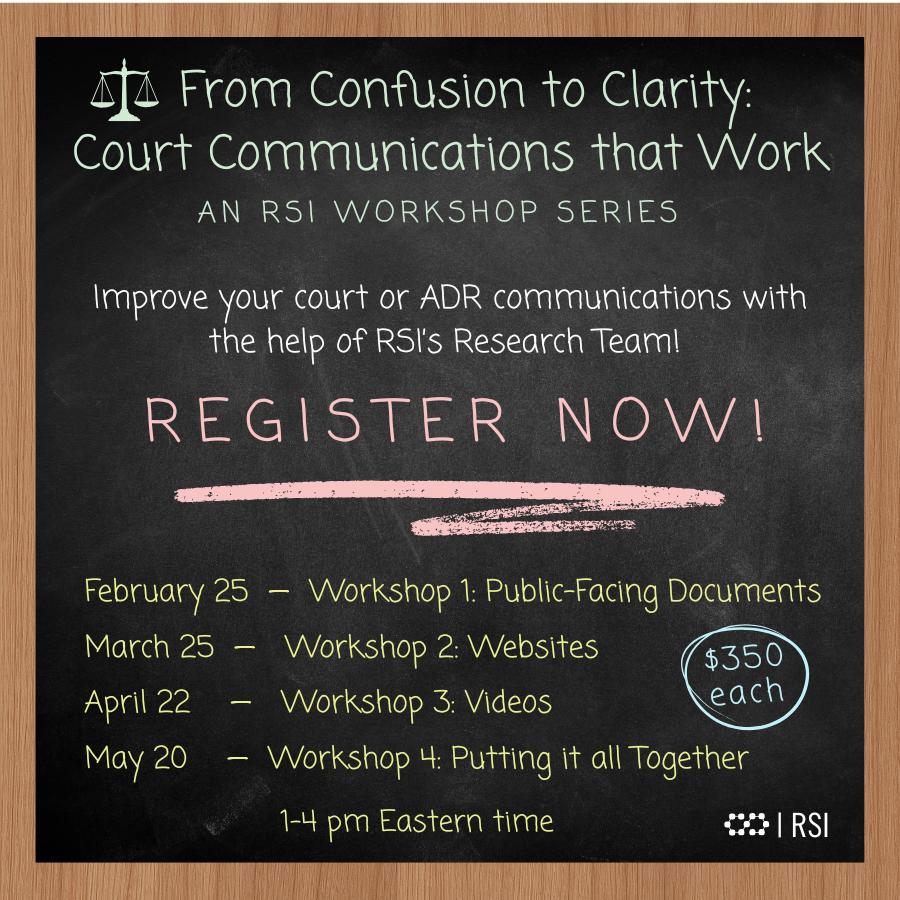

RSI is offering a series of online workshops to help courts and organizations enhance their ADR program communication materials. During these workshops — From Confusion to Clarity: Court Communications that Work — RSI’s researchers will work with participants to review and improve their communication materials, including notices, webpages and videos. Participants will walk away with new or updated materials and the strategies to ensure future communications can effectively serve their communities, including self-represented litigants (SRLs).

Improving Court Experience Remains a Priority

Courts continue to face diminished public trust and a lack of confidence among those who go through the legal system. The 2025 State of the State Courts report by the National Center for State Courts found that poor communications are a major driver of access to justice issues. People find court forms and paperwork confusing or hard to understand, and they lack information about what to expect from court processes, the report notes. In line with these findings, a recent Pew study on perceptions of state and local courts found that US adults want courts to be easier to navigate, to work for all users and to be more user-friendly.

According to the Pew study, one-third of people who have had a court experience emerged with diminished confidence in the courts. More than half of those with court experience found it difficult to understand how to fill out court forms and to understand the steps of their cases. The latter finding held true across demographic groups, including age, education level and income level, and regardless of whether the respondent was a plaintiff or defendant.

Most people also said courts should focus on making processes easier to navigate rather than making them faster. The same Pew study found that 71% of survey respondents with court experience and 68% of survey respondents without court experience said courts should make it easier for people to navigate the system rather than diverting their resources to speed up cases and reduce costs.

Why We Designed the Workshops

RSI’s OPEN research demonstrates that simple and easy-to-understand communications can meaningfully address some of the biggest challenges facing court users. Through usability testing, we found that our accessibly designed OPEN communication models boosted people’s confidence in navigating their case and enabled them to more capably follow the steps required to participate in ADR programs.

Easy-to-understand court communications are especially important for SRLs, people with low literacy and people with low digital literacy. Courts can make important inroads to improving court experience and building trust by addressing barriers in their communication materials. Our OPEN research also highlights scaffolding as an effective strategy for making the steps within court programs easy to follow.

Yet RSI recognizes that courts may not have sufficient resources for a full consultation to improve their materials. We developed these workshops to be low-cost opportunities for court staff to begin addressing these issues. By participating in our workshops, participants can take the first step to improving their existing communication materials or creating new materials that better serve their communities.

What the Workshops Will Cover

We are offering four workshops over the next few months. Each workshop will be 3 hours long and cost $350. Each will take place 12-3 pm Central/1-4 pm Eastern, via Zoom. Below are descriptions of each workshop:

Wednesday, February 25 — Workshop 1: Public-Facing Documents. Bring the documents you would like to modify or thoughts on what you want to create. You will leave with documents that are written and formatted so that SRLs will understand and act on any instructions. Register & pay now for Workshop 1, or Register & receive an invoice for Workshop 1. Please register by February 18.

Wednesday, March 25 — Workshop 2: Websites. Bring your webpages or ideas. Leave with a layout and draft content you can bring to your IT department. Register & pay now for Workshop 2, or Register & receive an invoice for Workshop 2. Please register by March 18.

Wednesday, April 22 — Workshop 3: Videos. We will help you take your ideas for a video and turn them into a storyboard to provide your communications department or consultant, or ready for you to create your own video. Register & pay now for Workshop 3, or Register & receive an invoice for Workshop 3. Please register by April 15.

Wednesday, May 20 — Workshop 4: Putting it All Together. Learn how to take your different communication methods and turn them into a workflow that enhances SRL trust and confidence in navigating an unfamiliar process. Register & pay now for Workshop 4, or Register & receive an invoice for Workshop 4. Please register by May 13.

We are excited to use what we have learned through the OPEN Project to help you with your communication needs. Please reach out to research@aboutrsi.org for any questions you may have about the workshops.